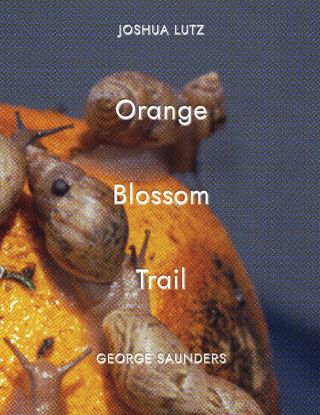

Source: Courtesy of Joshua Lutz

I recently exchanged some questions with Joshua Lutz about finding meaning in photography and his new book. Lutz is an artist and educator working primarily in photography and writing. His monographs include Be careful of the gap (2018, Schilt), Hesitant beauty (2013, Schilt) e Meadows (2008, Power Plant). His new book is Orange Blossom Trail (2024), a collection of photos interspersed with three texts by novelist George Saunders. Lutz has served on the MFA program faculty at Bard College, the International Center of Photography, and the Pratt Institute. He is an associate professor and chair of photography at Purchase College and co-founder of its contemplative studies program. An exhibition based on his new book opens at CLAMP gallery in New York City on November 7.

Marco Bertin: Can you tell us something about what contemplative photography means to you?

Joshua Lutz: You’re getting me in trouble right from the start with this! There are many great books out there that define contemplative photography in different ways than I do. The term was probably coined by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who used photography as a tool for awareness. His approach focused on moving away from trying to capture the perfect shot and encouraged photographers to be present with what was in front of them, free from distractions. Imagine the experience of photographing a stop sign that is not about the word STOP but about a focus of attention on the texture of the sign and the light reflected from the object. I find it useful to define this practice as “mindful photography”, that is, using the camera as a way to remain anchored to the perception of the present moment.

I define “contemplative photography” as something broader. It goes beyond being present and extends to a deeper awareness of the world around us. It’s not just about a perceptual visual experience, but also about considering what’s happening in the larger world: our internal struggles, the suffering of the planet, and the interconnectedness of everything. In this sense, contemplative photography captures something broader and becomes a more direct reflection of the experience of reality in a complete and direct way. It also recognizes how photographs work, what they do and, more importantly, what they don’t do.

MB: So what do photographs do and what don’t they do?

JL: Photographs are very effective at capturing light reflected from objects. This is part of what makes photography such a great mindfulness tool: it brings us back to the immediacy of the moment, to the literal light and form in front of us in the present moment. But beyond that, photographs are extraordinarily good at telling stories. These stories are usually based on some version of the truth, although the fun part of working with images is exploring what that truth actually is. Where things get really interesting is how incredibly convincing they are in making us believe that the truth is more than just the reflection of light off objects.

Source: Courtesy of Joshua Lutz

MB: How does all this relate to your new book?

JL: The new book certainly started with a mindful photographic approach and evolved into a contemplative practice. On the one hand, I use photography as a way to calm my mind and focus my attention. I spent years visiting this area of Central Florida called The Orange Blossom Trail. Initially, I simply walked around and observed, drawn to simple things like color and contrast. As time went on, though, my approach evolved as I started setting more intentions, trying to understand what was really happening in this space.

Throughout the process, I was also grappling with my own concerns as I used photography to look more deeply into the difficulties unfolding along the way. It has become a way not only to document but also to tell the stories of this area, through images that speak both to what you see and perhaps also to what is beneath the surface.

MB: How do George Saunders’ stories fit in?

JL: They certainly suit the contemplative side more than the mindful approach. The stories in the book create a narrative arc that touches on birth, labor, illness and death, intertwining ideas of impermanence, attachment, aversion and attachment. These stories aren’t just about a specific moment in time; they’re about how we relate to the world and the stories we tell ourselves.

The first story reflects on the randomness of birth and its effect on the trajectory of life. The second delves into moral responsibility and the human cost of progress, almost as an allegory of how social and economic growth overshadows individual suffering. The latest is a haunting look at impermanence, showing how we grasp and hold on, both literally and metaphorically. These are not isolated reflections but intertwined with the broader themes I am exploring in the book.

Source: Ithaca Press

MB: I read recently that the act of taking photos with our phones makes it less likely that we will retain any real memory of an event. Our memory becomes the photo. What do you think people can do to balance taking fun photos but also living life and making memories?

JL: You should focus on taking the photo, especially if it’s a selfie, and not worry about the memory. As long as you can post a great shot, that’s what matters. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Essential readings for awareness

This is difficult and my feelings about it have changed over time. I was quite critical, I saw crowds of people taking photos and I thought I was the one really present in that moment. But looking back, there are times when it would have been nice to take a photo.

Like everything, it’s about balance and finding a middle ground. One simple thing you can do is set your intention before taking a photo. Pause for a moment, set that intention, then put the phone away… or not.

#Awareness #contemplative #photography